It just takes one

Going into my third year of college, at Western Carolina University, felt like it was going to be the peak of my existence, or at least my college existence. I was going to be a Resident Assistant for my favorite resident director in my favorite dorm, I’d soon be turning 21, and Beyonce’s first solo album had just came out. I was ridin’ high.

And then I got my first writing assignment, on utilitarianism, in one of my first philosophy classes, which I’d mainly taken because several friends were in the class. Our professor, Dr. Scott, handed out the graded papers at the end of class one day, and I never got mine back. The bell rang, and then Dr. Scott asked me to hang back to chat for a few minutes. My heart dropped to the floor. He handed me my graded paper, and it was an F. I was gutted.

But then something unexpected happen. Dr. Scott, with his soft voice, kind eyes and quiet demeanor, told me he was going to do something that he rarely let any student do. He was going to give me a chance to write the paper from scratch, and that he’d grade it as if it was my first writing assignment. He told me that he believed in me, and that he knew that my paper wasn’t reflective of my ability.

At another time in life, when I hadn’t closed myself off to emotion, I probably would’ve just dropped to my knees and started balling my eyes out. Dr. Scott gave me a few pointers, and sent me on my way. It was a kindness, tenderness and a second chance that I hadn’t felt like I’d received from men. It was the first of many by my philosophy teachers.

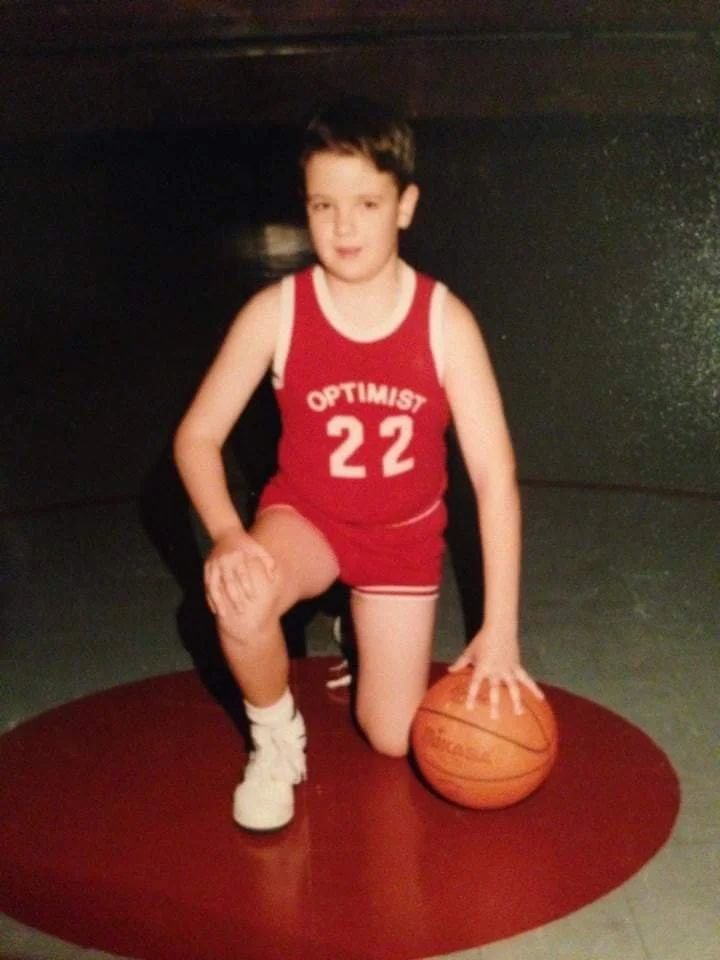

With the exception of a few men, like basketball coaches, friends’ dads, and my brother-in-law, my model of masculinity and manhood as a child is what the kids these days may call a dumpster fire. When I think of so many of the bad characteristics to describe men and masculinity, like abuse, infidelity, control, narcissism, anger, and compulsiveness, these characteristics were on full display from so many of the men of my childhood.

For example, I’ll never forget my mom sitting me down when I was in elementary school, and asking me a series of questions after an assistant coach I’d had was arrested for numerous counts of child sexual abuse.

And then there are the memories I suppressed and dissociated from, and have only recently recalled, like when I took swimming lessons as a young kid, and was forcibly removed from the pool area and shamed because I was too afraid to dive in the deep end. It felt like I was getting punished simply because I wasn’t comfortable enough in the deep end of the pool. I was 5 years old. I was being punished, and punished in front of my peers, for being a kid. And all the times I was told I threw like a girl, or told to man up or told to grow a pair or told to stop being so emotional. Or the times I was demeaned and sworn at because I didn’t know how to do something. I was a child.

Arguably my all-time favorite book about masculinity is bell hooks’ The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. As far as I’m concerned it should be required reading. This is what bell writes:

“Learning to wear a mask (that word already embedded in the term “masculinity”) is the first lesson in patriarchal masculinity that a boy learns. He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male. Asked to give up the true self in order to realize the patriarchal ideal, boys learn self-betrayal early and are rewarded for these acts of soul murder.” — bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love

I keep thinking about all the soul murder and self-betrayal I went through as a child, and worse, all of the boys who grow up in a culture and system that punishes them for being themselves, showing emotion, and/or not living up to the masculine ideal, which is often characterized by power, domination, anger, violence, and performance. As hooks writes, “In patriarchal culture males are not allowed simply to be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do.”

Twenty years ago, when Dr. Scott spoke to me with such kindness, and gave me a second chance, he challenged my view of masculinity. I honestly was apprehensive at it. I feel like I may have even asked him what the catch was; I didn’t believe that he was just giving me a second chance because he believed in me and cared for me.

Begrudgingly, and against every stubborn fiber in my body, I went to one of my friends in class, a Philosophy major who was Dr. Scott’s mentee, and told her what happened. She backed Dr. Scott’s words and character, and gave me some additional tips, and proofread my paper before I very nervously turned it in.

The following week in class, Dr. Scott was lecturing on utilitarianism when he pulled out a paper that he remarked spelled out his point particularly well. As he started reading the words, I immediately recognized them. They were my own words. He handed it to me. It was a grade of a 97, an A+, and one of the highest grades he’d given on a paper.

As I wrote this last paragraph, my eyes welled up at the power of that moment and experience. The following summer, I housesat for Dr. Scott’s house for a week, and he became the closest thing to a mentoring professor that I ever had.

My senior year I changed my major from Physical Education to Philosophy, and started opening up to my male professors in ways that I hadn’t been able to open up to older males. Later that year I had my first-ever writing published, in the school’s satire publication, The Gadfly. A couple years later I spontaneously one Friday afternoon sent off an article to an editor of a magazine to ask for feedback. I sheepishly asked if they thought I could have a future as a writer. The next day they published it in their magazine that had a circulation of thousands of readers. Fast-forward nearly two decades and I’ve made a career as a writer and editor.

Words matter. And the words, and investment and kindness of Dr. Scott really mattered. In the coming days, a lot of what I write here will be about my journey of self-discovery in recent years, and especially the last year. And much of that journey has been one of unlearning and redefining not just what it means to exist in the world, but what it exists to be in this body as a man, and all of the experiences, moments, and emotions that have shaped me and that will continue to shape me. This is who I aspire to be…

“For both men and women, Good Men can be somewhat disturbing to be around because they usually do not act in ways associated with typical men; they listen more than they talk; they self-reflect on their behavior and motives, they actively educate themselves about women’s reality by seeking out women’s culture and listening to women…. They avoid using women for vicarious emotional expression…. When they err—and they do err—they look to women for guidance, and receive criticism with gratitude. They practice enduring uncertainty while waiting for a new way of being to reveal previously unconsidered alternatives to controlling and abusive behavior. They intervene in other men’s misogynist behavior, even when women are not present, and they work hard to recognize and challenge their own. Perhaps most amazingly, Good Men perceive the value of a feminist practice for themselves, and they advocate it not because it’s politically correct, or because they want women to like them, or even because they want women to have equality, but because they understand that male privilege prevents them not only from becoming whole, authentic human beings but also from knowing the truth about the world…. They offer proof that men can change.” — bell hooks, The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love